Nav

This

Blog

More

Settings

An Intro to Programming with Lua and TIC - Part 1

Contents

You are standing in front of a screen that purports to get you to dip your toes into making tiny games.

What will you do?

> Stay to hear an intro. Whet my palate.

> Jump right into it.

intro

i fucking looooove programming. i annoy everyone around me with it. it’s been a big part of how i think and create these past few years, and i’d love to share the fun of it with you.

i’ll assume you have no experience ever touching code before! so, we’ll go through pretty much everything you need to know, and if you don’t understand something yet, you can reasonably assume i’ll touch up on it later. be curious, play with patterns; change code to see what’s possible, watch what happens when you poke around.

in this tutorial, i’ll be using:

Lua, for being a tiny but powerful scripting language that’s used in a lot of different places, from games to web frameworks to academic research. if you’re interested in something, there’s a chance you can do it with Lua.

TIC-80, for being a free tool for making small retro games, complete with editors for code, graphics and sound (if you know the PICO-8, it’s a clone of that).

learning to code has opened up lots of new possibilities to make things for myself and others, like videogame mods based on inside jokes, automation scripts for boring computer tasks, app customization, etc.

even disregarding that, it’s not just a means to an end. it’s my opinion that programming is a very satisfying and fun craft in its own right. artistically speaking, it’s very efficient: as the artist’s quest is to be eternally dissatisfied, knowing how to program vastly increases the amount of projects you want to do but don’t have time for.

but first.

we need a goal

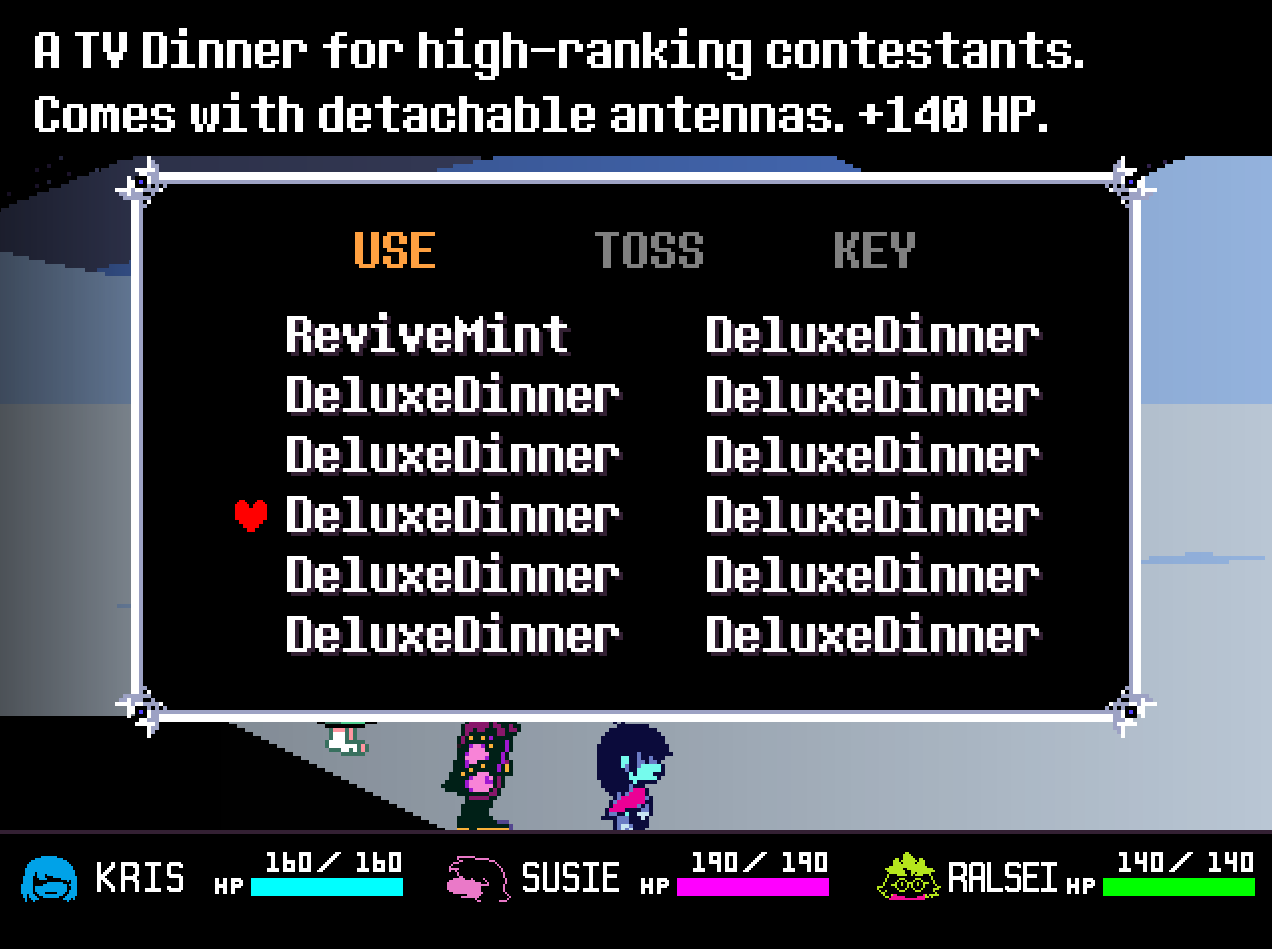

learning - anything, mostly, but also programming - works best when you have a goal to work toward. personally? i love a Good User Interface (they call this a “GUI”). a juicy, satisfying GUI begs you to flick switches and press buttons just to see them react. so let’s work up to building one like in Deltarune:

we have a list of items, with an indicator of which item is currently selected, and a short sentence describing that item.

so… we’ll have to find a way to store a list of items with self-contained data, draw some text, draw sprites, maybe a box around it? sounds complicated, but as with everything, you build it up piece by piece.

let’s begin

open up https://tic80.com/create. you can click “Click to Play,” or download and open it. when it loads up, hit Esc to bring up the code editor, then Ctrl + A to select all text, and Backspace to clear out the default code. this is our playground environment!

inside it, write the following:

function TIC() exit() endthis is just code that terminates the game when it’s finished running, we’ll replace it soon.

Lua reads pretty close to plain english, so we can create a variable with a name and store something in it with the “assignment operator” =, followed by some data.

phrase = "hello, world"

function TIC() exit() endwe can retreieve the stored value by just typing the variable’s name. for example, we can show its contents with trace(), a function that prints out some data.

the variable gets “value-ified,” or “evaluated,” and you can use it as though you’d just written its contents out manually.

phrase = "hello, world"

trace(phrase, 5)

function TIC() exit() endpress Ctrl + R to run your game. you should see

> "hello, world"in a lime-green color. neat!

this is the console of TIC-80, and it’s a basic interface to input commands OR see code outputs. try it out! type cls, then hit Enter to submit the screen-clearing command.

variables, values, data

you’ve already put something inside a variable. these bits of standalone data are called “values,” and when you type them out directly into the code (as opposed to, say, extracting them from an online database), that’s called a “value literal.”

Lua has a few different kinds of values, including (but not limited to):

- numbers:

1,-5,10.5(and the usual numerical operators+-/*); - strings, representing text:

"hello, world!","Sword","anim_idle"(and the “concatenation” operator to join strings together,..); - booleans, which represent an ON/OFF switch state:

true,false(and some comparison operators we’ll see later);

all values have a specific internal “type” that dictates what actions you can do on it. for example, addition doesn’t work on strings.

trace(1 + 2) -- output: 3

trace("hello" + 1) -- error! you can't do addition on a string.

trace(5 + 6) -- output: 11…but hey wait, what’s “doesn’t work” mean? let’s run the game and see.

ah, interesting. so when an error comes up, it kicks you back to the console and writes out an error message in red. the message tells us what Lua’s complaining about: “attempt to perform arithmetic on a string value” means “tried to do math on a string.” the :2: part tells us that the error happened in line 2. helpful!

also, did you notice how it printed out 3, but not 11? it looks like when an error occurs, our program’s execution is halted on the spot, so it never even got to trace(5 + 6). that’s good to know.

functions

another type of value are “functions,” little self-contained bundles of code that you can store in a variable and carry around.

you’ve already been using them - trace() - and you can create your own with function() end.

my_func = function() endyou can then put lines of code inside it:

my_func = function()

trace("hello!")

endthat code now lives in that new function… which is stored inside a variable. when you use parentheses () on a variable name, it “calls” the computer over and says “hey, there’s a function here! come run its code.” this is how you “call” a function.

my_func() -- output: testthis means that, for example, instead of copying out code multiple times for a common operation, you can put that code inside a function and call it whenever you need it.

trace() is also a function! hidden inside, there’s code for setting up text data, font and coloring, and printing it to the screen. but because it’s inside a function, you, the caller, don’t need to worry about any of that; the underlying complexity is hidden away and replaced with functionality.

but this is a bit text-y, it’s not… tangible, visible. we can get much more graphic in a second.

arguments, scope

before we move on, you should know that code reuse is just 1/3 of what makes functions so useful. the second part is “arguments:” values that you supply to the function at call-time, and so may change every time you call a function.

to create a function that takes arguments, just write however many variable names in the parentheses when creating it:

my_func = function(arg, other_arg, third_arg) endyou can now use those just like variables. type their name to retrieve their values.

my_func = function(arg, other_arg, third_arg)

trace(arg)

trace(arg + other_arg)

trace(arg + third_arg)

endthen, when you actually call the function to execute it, you can put values inside the parentheses, and it’ll automatically supply them to the current call, like each call is its own little sandbox with its own values to work with.

-- for this call, inside my_func, "arg" becomes 10, "other_arg" becomes

-- 2, and "third_arg" becomes 4.

my_func(10, 2, 4)

trace("***")

-- for this call, all of those get set to different numbers.

my_func(20, 1, 3)output:

> 10

> 12

> 14

> ***

> 20

> 21

> 23you can think of this as an automated version of creating a new set of variables every time you call this function. these special variables are exclusive to this function, and they auto-delete themselves when the function finishes running, so you can’t access them from the “outside,” per se. watch:

my_func = function(arg)

trace("inside, arg is:")

trace(arg)

end

my_func("hi!") -- execute my_func with the argument "hi!"

trace("outside, arg is:")

trace(arg)

…wait, nil?

nil

right, so, nil is a special, unique value that signifies the absence of meaningful data. this is how the computer tells you “nothing useful here.” trying to access a value that doesn’t exist yet gives you nil.

trace(unitialized_variable) -- output: niland operations with nil usually give you errors - this is Lua’s way of preventing you from doing bogus operations on incorrect data (e.g. misspelling a variable name).

my_func = function() end

my_fnuc() -- error! can't call "nil" like a function.

trace(1 + nil) -- error! can't perform arithmetic on "nil".back to arguments

at first glance, variables that you can only access from within a function seem like a limitation, but it’s actually very helpful! if arguments could “leak” from one function to another, with every function changing the same variable back and forth, it could get extremely difficult to keep track of everything. self-contained variables make sure you can share names across functions (and even across files!) safely.

so now that you know what arguments are, we can look at how built-in functions, like trace(), uses them to work their magic. trace() sets up all the text-handling state behind the scenes, then just takes your argument and actually prints it.

-- in TIC-80, 2 is the color-code for red

trace("red text", 2)

so this is nice and compact! trace() represents a whole action, “print this text to the screen, with this color,” which might have lots of complicated internal code, but using arguments, you can just tell it which text and which color to use, and it does its job.

and this is just for printing text to the console! TIC has many, many functions to do all sorts of things, like drawing shapes, querying button inputs, messing with the memory, etc.

this is your key to power.

something visual

our boilerplate code introduced a new function, named TIC(), that gets called 60 times a second. each of these times represent a frame. (60 frames per second? where have i heard that before?)

previously, we just called exit() inside it, which immediately closes the game. but what if we, say, use cls() to clear the screen?

color_code_red = 2

function TIC()

cls(color_code_red)

end

then draw a circle?

color_code_red = 2

color_code_white = 12

circle_horizontal_position = 120

circle_vertical_position = 68

circle_radius = 20

function TIC()

cls(color_code_red)

circ(

circle_horizontal_position,

circle_vertical_position,

circle_radius,

color_code_white

)

end

and copy-paste it… hm, 63 times

color_code_red = 2

color_code_white = 12

circle_horizontal_position = 120

circle_vertical_position = 68

circle_radius = 20

function TIC()

cls(color_code_red)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 31, circle_vertical_position - 31, circle_radius, color_code_white - 31)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 30, circle_vertical_position - 30, circle_radius, color_code_white - 30)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 29, circle_vertical_position - 29, circle_radius, color_code_white - 29)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 28, circle_vertical_position - 28, circle_radius, color_code_white - 28)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 27, circle_vertical_position - 27, circle_radius, color_code_white - 27)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 26, circle_vertical_position - 26, circle_radius, color_code_white - 26)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 25, circle_vertical_position - 25, circle_radius, color_code_white - 25)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 24, circle_vertical_position - 24, circle_radius, color_code_white - 24)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 23, circle_vertical_position - 23, circle_radius, color_code_white - 23)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 22, circle_vertical_position - 22, circle_radius, color_code_white - 22)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 21, circle_vertical_position - 21, circle_radius, color_code_white - 21)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 20, circle_vertical_position - 20, circle_radius, color_code_white - 20)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 19, circle_vertical_position - 19, circle_radius, color_code_white - 19)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 18, circle_vertical_position - 18, circle_radius, color_code_white - 18)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 17, circle_vertical_position - 17, circle_radius, color_code_white - 17)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 16, circle_vertical_position - 16, circle_radius, color_code_white - 16)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 15, circle_vertical_position - 15, circle_radius, color_code_white - 15)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 14, circle_vertical_position - 14, circle_radius, color_code_white - 14)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 13, circle_vertical_position - 13, circle_radius, color_code_white - 13)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 12, circle_vertical_position - 12, circle_radius, color_code_white - 12)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 11, circle_vertical_position - 11, circle_radius, color_code_white - 11)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 10, circle_vertical_position - 10, circle_radius, color_code_white - 10)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 9, circle_vertical_position - 9, circle_radius, color_code_white - 9)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 8, circle_vertical_position - 8, circle_radius, color_code_white - 8)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 7, circle_vertical_position - 7, circle_radius, color_code_white - 7)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 6, circle_vertical_position - 6, circle_radius, color_code_white - 6)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 5, circle_vertical_position - 5, circle_radius, color_code_white - 5)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 4, circle_vertical_position - 4, circle_radius, color_code_white - 4)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 3, circle_vertical_position - 3, circle_radius, color_code_white - 3)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 2, circle_vertical_position - 2, circle_radius, color_code_white - 2)

circ(circle_horizontal_position - 1, circle_vertical_position - 1, circle_radius, color_code_white - 1)

circ(circle_horizontal_position, circle_vertical_position, circle_radius, color_code_white)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 1, circle_vertical_position + 1, circle_radius, color_code_white + 1)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 2, circle_vertical_position + 2, circle_radius, color_code_white + 2)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 3, circle_vertical_position + 3, circle_radius, color_code_white + 3)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 4, circle_vertical_position + 4, circle_radius, color_code_white + 4)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 5, circle_vertical_position + 5, circle_radius, color_code_white + 5)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 6, circle_vertical_position + 6, circle_radius, color_code_white + 6)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 7, circle_vertical_position + 7, circle_radius, color_code_white + 7)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 8, circle_vertical_position + 8, circle_radius, color_code_white + 8)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 9, circle_vertical_position + 9, circle_radius, color_code_white + 9)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 10, circle_vertical_position + 10, circle_radius, color_code_white + 10)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 11, circle_vertical_position + 11, circle_radius, color_code_white + 11)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 12, circle_vertical_position + 12, circle_radius, color_code_white + 12)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 13, circle_vertical_position + 13, circle_radius, color_code_white + 13)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 14, circle_vertical_position + 14, circle_radius, color_code_white + 14)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 15, circle_vertical_position + 15, circle_radius, color_code_white + 15)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 16, circle_vertical_position + 16, circle_radius, color_code_white + 16)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 17, circle_vertical_position + 17, circle_radius, color_code_white + 17)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 18, circle_vertical_position + 18, circle_radius, color_code_white + 18)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 19, circle_vertical_position + 19, circle_radius, color_code_white + 19)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 20, circle_vertical_position + 20, circle_radius, color_code_white + 20)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 21, circle_vertical_position + 21, circle_radius, color_code_white + 21)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 22, circle_vertical_position + 22, circle_radius, color_code_white + 22)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 23, circle_vertical_position + 23, circle_radius, color_code_white + 23)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 24, circle_vertical_position + 24, circle_radius, color_code_white + 24)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 25, circle_vertical_position + 25, circle_radius, color_code_white + 25)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 26, circle_vertical_position + 26, circle_radius, color_code_white + 26)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 27, circle_vertical_position + 27, circle_radius, color_code_white + 27)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 28, circle_vertical_position + 28, circle_radius, color_code_white + 28)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 29, circle_vertical_position + 29, circle_radius, color_code_white + 29)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 30, circle_vertical_position + 30, circle_radius, color_code_white + 30)

circ(circle_horizontal_position + 31, circle_vertical_position + 31, circle_radius, color_code_white + 31)

end

ah… er. well, there must be an easier way to do this. keep your eyes peeled.

comparisons, conditions

bear with me here. Lua provides you with a few “comparison operators” that take 2 values and produce a boolean; the primary one being the “equality comparison operator” ==.

(make sure not to confuse it with the assignment operator =.)

it evaluates to true when both sides evaluate to the exact same thing, and false otherwise:

trace(1 == 1) -- output: true

trace(5 == 5.1) -- output: false

trace(10 == "10") -- output: false

trace(false == false) -- output: truea lot of constructs in programming work with booleans, such as the if statement, which only executes its containing block of code if its condition evaluates to true, otherwise it’s completely skipped:

x = 1

if x == 0 then

trace("x is 0!")

end

if x == 1 then

trace("x is 1!")

end

trace("finished.")output:

> x is 1!

> finished.these are “control statements,” special constructs that control how code is executed.

if has two optional extensions: elseif, which executes if all previous conditions failed and its own condition succeeded, and else, which always executes if all previous conditions failed. here.

x = 1

if x == 0 then

trace("x is 0.")

elseif x == 1 then

trace("x is 1.")

else

trace("x is something else!")

end

trace("end")output:

> x is 1.reads pretty naturally, right? if x is 0, then do this. else if x is 1, do that. else, do another thing.

extra details:

- only one of the code blocks in an

if/elseif/elsecollection can ever execute. - you can chain multiple

elseifs one after another, however many times you need.

if cond then

...

elseif other_cond then

...

elseif third_cond then

...

endreturn values

the last thing we really need to know to get things going for real are “return values.” you see, function-calls themselves can turn into values with the return keyword.

return, when used inside a function, immediately halts its execution. simple enough.

my_func = function()

trace("start of function")

return

trace("unreachable trace")

end

my_func()

trace("done")output:

> start of function

> donehowever! putting a value after the return makes it so that the function call evaluates to that value. like this, see:

function my_func()

return 10

end

trace(my_func()) -- output: 10this has some pretty far-reaching ramifications because it means any function can be its own tiny input-output system, receiving data and working with it to produce some meaningful result.

e.g. we can use return values to make a function that produces the double of a number:

double = function(num)

return num * 2

end

trace(double(783)) -- output: 1566or one that greets people:

greet = function(name)

-- the "concatenation operator" joins strings together: ".."

return "Hello, " .. name .. "!"

end

john_greeting = greet("John")

rose_greeting = greet("Rose")

trace(john_greeting) -- output: hello, John!

trace(rose_greeting) -- output: hello, Rose!…hmmmm…

trace(greet(greet("Dave"))) -- output: hello, hello, Dave!!hehehe.

either way, these 2 things: arguments and return values mean every function can be a self-contained little program that acts as a tiny, reusable piece of functionality. you can give it some information, and it’ll hand you back something relevant.

let’s query some input state!

all this talking! explaining! i want things to happen!

btn() is a TIC function that…

…you know what, why don’t we let it tell us?

in the console, the help command gives you help about a specific topic - including which functions are available for you to use, and what they do.

we can do help btn to see some information about btn():

okay, so we can see that btn() takes in a single argument, named id, and returns a single value, pressed. it tells us that it returns true if the key with the supplied id is currently held down.

we can get a list of buttons with help buttons.

so it seems that… “up” is ID 0 and “down” is ID 1.

let’s take it back to the code editor, and set up a position variable.

vertical_position = 68

function TIC() exit() endinstead of exiting, we’ll draw a circle with position… uh, how do you draw a circle again?

x and y are computer shorthands for “horizontal position” and “vertical position,” respectively.

so i guess on each frame, we can draw a circle at x value 0, and the y value will be our vertical_position… the 3rd argument is the radius, and the 4th is color.

vertical_position = 68

function TIC()

-- draw a circle with radius 15 and color code 2 (red)

circ(120, vertical_position, 15, 2)

endoh, and each time, wipe the screen to color code 0 (black) before we draw the circle.

vertical_position = 68

function TIC()

cls(0)

circ(120, vertical_position, 15, 2)

endbut actually, if you look at the help entry for cls()…

if you don’t supply an argument, it uses 0 as the default anyway, so we don’t need it.

vertical_position = 68

function TIC()

cls()

circ(120, vertical_position, 15, 2)

endlet’s run it.

ok, now we can make use of the input state!

since btn() checks if a button is held down, and evaluates to true if it is, we can use it inside an if statement.

so each frame, if button with ID 0, up, is pressed, we can set vertical_position to itself minus one. this is equivalent to just subtracting 1 from it.

vertical_position = 68

function TIC()

if btn(0) then

vertical_position = vertical_position - 1

end

cls()

circ(120, vertical_position, 15, 2)

endand we can do the same for button 1, down, except we add 1.

we do it this way because, in TIC’s coordinate system, as a point moves further along the vertical axis, it goes down. this means positive-Y is down, and negative-Y is up.

vertical_position = 68

function TIC()

if btn(0) then

vertical_position = vertical_position - 1

end

if btn(1) then

vertical_position = vertical_position + 1

end

cls()

circ(120, vertical_position, 15, 2)

endnow you can control your circle with the arrow keys! hooray!

particles = {}

vertical_position = 68

function TIC()

table.insert(particles, math.random() * 240)

cls()

for y, x in ipairs(particles) do

particles[y] = x + (math.random() > 0.5 and -1 or 1)

pix(x, -y + time() * 0.05, math.random() * 15)

end

if btn(0) then

vertical_position = vertical_position - 1

end

if btn(1) then

vertical_position = vertical_position + 1

end

circ(120, vertical_position, 15, 2)

end

for you, who’s come so far, a complimentary version of this code that includes confetti, if you wanna paste it on your own TIC:

view code-- don't worry about understanding any of this yet

particles = {}

vertical_position = 68

function TIC()

table.insert(particles, math.random() * 240)

cls()

for y, x in ipairs(particles) do

particles[y] = x + (math.random() > 0.5 and -1 or 1)

pix(x, -y + time() * 0.05, math.random() * 15)

end

if btn(0) then

vertical_position = vertical_position - 1

end

if btn(1) then

vertical_position = vertical_position + 1

end

circ(120, vertical_position, 15, 2)

endwrap up

i have to cut myself off from making this tutorial a 6 month project. please appreciate how far this already is: we covered the basics of Lua and TIC, variables, values, functions, arguments, comparisons, conditions, input… it’s a lot already. have you been taking notes?

in the next chapter, we’ll explore some more types and constructs that’ll unlock more of Lua’s power to you. until then, you’ve probably learned enough to try messing around with the code a little bit on your own. can you figure out how to make the circle move sideways? what about full 8-directional movement, with diagonals? maybe you’re feeling confident enough to flip through the Lua manual and see what else the language offers?

thanks for reading either way.